Influence and Homage

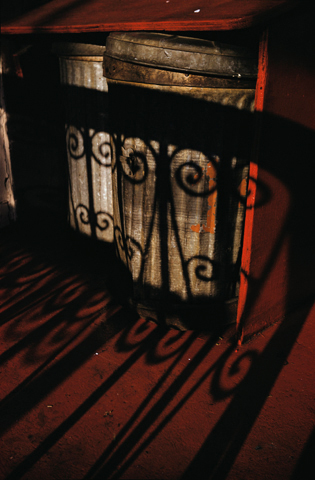

Alley Door, Santa Fe 2010 . Mike Broadway

Monday’s post on the The Online Photographer alerted me to the fact that a new book of Ernst Haas photographs, “Color Correction,” has been produced by Steidl. I placed my order with Amazon before the day was out and received it Wednesday, courtesy of the ‘free’ two day shipping on my wife’s Prime account.

Despite having seven or eight feet of shelf space devoted to photography books, this is the first I have been motivated to buy in five years or more. The book now in my hands was worth breaking the moratorium for; Haas is not often listed on the same page with the 20th century greats but he darn well should be.

For some the book will be problematic in that the selection was not made by Haas himself; he died in 1986. Haas left no list saying that these images should be considered as part of his canon; he did not print or sign or designate them in any way. The selection was made by William A Ewing, a well known curator and director of Musee de l’Elysee in Lausanne, Switzerland. Few would argue about Ewing’s qualifications for the job but still the question will remain: are we looking at a collection authored by Haas or the creation of a curator pulling from the reject bin?

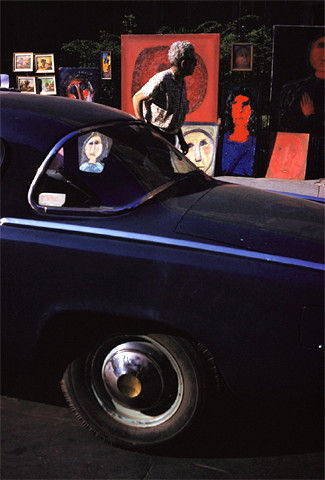

Greenwich Village, New York, 1950s . Ernst Haas |

New York, 1952 . Ernst Haas |

The same argument might be leveled against the presentation of Da Vinci’s notebooks or Rembrandt’s sketches but you won’t hear it. That Haas did not exhibit these images during his life time does not, of necessity, exclude them from being recognized as his intentional art. It is true that machine produced photography must be judged according to different criteria than the hand drawn sketches of a master; it is too easy for a casual snap to be interpreted as ground breaking art by an overly eager interpreter. A Chimpanzee’s oil painting is not art no matter how much it looks like a modernist work that Clement Greenberg would have championed. But Haas was no chimp with a camera, he was a master photographer and arguably the first master of color photography. These images are not one off discards but present on almost every roll of film that the man exposed. These were not accidents but deliberate choices of framing and exposure that represented something important to the photographer, something that was on his mind even in the midst of commercial assignments.

If Haas were alive today I think he might have swapped one or two of Ewing’s selections for other images but all the work in the book is of a high standard and consistent in style and quality with pictures that he did publish. Many are reminiscent of Ralph Gibson (but in color), Lee Friedlander (but in color) and Joel Meyerowitz. They are not copies though, they were being made 10 years earlier than the work of these greats and there is always something unmistakably Ernst Haas about them. This book contains the work of artistic genius.

I choose to believe that Haas would have approved of this collection and signed his name to it but I am not an unbiased commentator. Haas was perhaps the most important influence on my thinking as I cut my camera teeth back in the late 70s. That was a long time ago and I did not realize how great that influence had been until I spent my first hour with this book. A thing of beauty by itself, the book is also a challenge and a teacher. A challenge to avoid mimicry of the Haas style and at the same time an encouragement not to fear the dark (under exposed, high contrast with large areas of black and near black).

You can find more of the images from the book online at the Ernst Haas estate web site under the “Collection of Newly Discovered Photographs” section. Articles about the book and selections of images can also be found at Visura Magazine (larger size than most sites), Time LightBox and the BBC.

There are 186 plates in the book, many more than you will find on any web site. The best way to see them, if you can afford it, is to buy the book from Amazon or pay a little more and keep your local store in business.